Pablo de Santa María

Selemoh ha-Leví, or Pablo de Santa María', initially Schlomo ben Jitzchaq ha-Levi (שלמה הלוי מבורגוס),[1] known as El Burgense (Burgos, around 1350-30 August 1435), was a poet, scholar and historian Spanish Spanish-Hebrew, Jew convert to Christianity, counselor of Enrique III, theological and biblical writer, bishop of Cartagena and commentator of Burgos. == Biography == He received a careful education in the Burgos Jewish school, from where he was a major rabbi, but, after the anti-Jewish revolt of 1391]] —known with the Central European term of [pogrom]]' or 'forced conversions of 5151' (corresponding year in the Hebrew calendar)—, started on June 6 of that year in Seville,[2] was converted by the preacher (saint)|Vicente Ferrer]] and, abandoning the Judaism, was baptized in the Catholic faith with the name of Pablo García de Santa María[3] in July 1390, shortly before the most terrible assaults on the Jewish wards of the entire Middle Ages in the year 1391. Having not wanted to become his wife, he separated judicially from her and educated his children, including the future humanist and bishop of Burgos Alfonso de Cartagena, in the Christian religion. His brother, Álvar García de Santa María, also converted. The ancient rabbi oriented himself towards Christian ecclesiastical life, studying theology in Paris and in Aviñón, city where the pontiff resided, who promoted him in 1395 to the dignity of archedian of Treviño (whose exercise had its headquarters in the Cathedral of Burgos, not in the County of Treviño). Enrique III proposed him for the bishopric of Cartagena (1401) and appointed him royal councilor and ayo of Prince Don Juan, future Juan II of Castile. In 1407, after the death of Pero López de Ayala, he was appointed chancellor mayor of Castile. He was also an advisor to Fernando de Antequera, king of Aragon. In 1415 he was elected bishop of Burgos. Two of his sons followed the ecclesiastical-political career, reaching various episcopal seats and responsibilities in Castilian politics: Alfonso de Cartagena and Gonzalo de Santa María. Months before his death he was appointed by Eugenius IV patriarch of Aquilea, being sueded in the Burgos headquarters by his son Alfonso, then royal ambassador at the Council of Basel. He moved away from courtly life and in his will left all his assets to the poor. He died on August 30, 1435 in the city of Burgos. His body was buried in the main chapel of the now disappeared convent of San Pablo de Burgos, of the Order of the Dominics. == Works == The seven ages of the world or Troubaded Ages is a poem in 339 coplas de arte major and verses dodecasílabos, in which the complete history of the world is made from the creation to the enthronization of the king Henri IV of Castile. It is dedicated to the mother of Juan II de Castilla Catalina de Lancáster in 1430, and although it was already composed according to its publisher Juan Carlos Conde between 1416 and 1418,[4] combining a story of universal history according to the topical seven ages of the world with a story of Castilian national history, he mentions the pope Calixtus III, who was only between 1455 and 1458, so what has come to us is a version of 1460 retouched, corrected and expanded after that date by an anonymous author, who also added comments and glosses in prose to other comments and glosses he already had. As for its formal aspects, it contains hardly any rhetorical ornaments: it looks like a versified and arid chronicle in a plain style. The work begins with a long exposition of Jewish history according to the Old Testament, then alternates the history of the Jews with a brief history of Greece, Rome and the Church, with the most important popes, and concludes with the history of the Visigothic kings and Castile by their monarchs, including his former pupil John II, whom he advises in terms of difficult interpretation and incites to conquer the kingdom of Granada. He does not mention the private don Álvaro de Luna. The poem was poorly attributed to Íñigo López de Mendoza, marqués de Santillana, when Eugenio de Ochoa printed it among the unpublished Rhymes of Don Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marqués de Santillana, of Fernán Pérez de Guzmán, Señor de Batres, and other poets of the 15th century (Paris: ed. of the author, impr. Fain and Thunot, 1844). Then it was edited by the Hispanic Raymond Foulché-Delbosc in the NBAE', XXII (1915) and the American Hispanicist M. Jean Sconza (Madison: HSMS, 1991), improving previous editions. Pablo de Santa María also wrote the Sum of Chronicles of Spain, the Generation of Jesus Christ and the Supper of the Lord. === Scrutinium Scripturarum === The 'Scrutinium Scripturarum contra perfidia iudaeorum' was composed in Latin at the end of his life, it is one for which it enjoys international fame, under the nickname of the "Burgense". He exposes in a dialogued way, first, the mistakes of the Jews, which he then refutes, and then explains the mysteries of the Christian faith. He reached several editions; the best known dates from 1591 and carries as a preamble his biography composed by Cristóbal de Santotis. From the same time are the aforementioned Additions ad postillam magistri Nicoali de Lyra super Bibliam (Additions to the Apostilles of the master Nicolas of Lira on the Bible) (1270-1340). == Pastoral work == He convened two synods. The one of 1418 reveals his interest in the correct formulation of the articles of the faith, revising the text of his predecessor Juan Cabeza de Vaca. The one of 1427 is of a pastoral and liturgical nature and had the participation of St. Bernardino of Siena. He financed part of the construction of the disappeared convent of San Pablo de Burgos, of the Order of the dominicos, strengthened the monastery of San Juan de Ortega carrying monks of Fresdelval, as well as San Miguel del Monte, next to Miranda de Ebro. In 1432 the monastery of claries of Nofuentes, dedicated to Our Lady of Rivas, received pontifical approval. == Relationship with Judaism == Pablo, who even after being baptized, continued to debate with several Jews, including Joseph Orabuena, chief rabbi of Navarra, and Joshua ibn Vives, became a bitter enemy of Judaism.[5] He did everything possible, frequently successfully, to convert their former co-religionists. With that same spirit and main purpose, as chancellor of the kingdom, he drafted an edict that was promulgated on behalf of one of the two regents: the widowed queen mother, Catalina de Lancaster, in Valladolid on January 2 (no. 12), to incite the conversion of the Jews of Castile. This law consisted of twenty-four articles aimed at completely separating Jews from Christians, paralyzing their trade and business, humiliating them and exposing them to contempt, forcing them to live in the narrow barracks of their guet or accepting the baptism. Driven by his hatred of Talmudic Judaism, he composed in the year before his death the Dialogus Pauli et Sauli contra judæos, the Scrutinium Scripturarum (Mantua, 1475, Mainz, 1478, Paris, 1507, 1535, Burgos, 1591), which served as a source to enfant the anti-Semitism of Alfonso de Spina, Gerónimo de Santa Fé and other Spanish writers hostile to the Jews, as well as that of Martin Luther in Germany, who composed under his inspiration the treatise 'On the Jews and their lies'. A few years after his baptism he wrote Additiones (which consist of additions to the postillas of Nicolás de Lira to the Bible, printed relatively frequently) and, already in his old age, a Universal History in Spanish verse, The Seven Ages of the World' or Troubad Ages. == Descendants == Along with him, his children and his mother were baptized. His firstborn, Gonzalo, was bishop of Astorga, of Plasencia and Sigüenza; while the third, Alonso, succeeded him in the headquarters of Burgos, an unusual fact, although not unique (see Spanish Clergy in the Old Regime). His wife would be baptized years later than him; and his father would never do it. Her granddaughter Teresa de Cartagena, daughter of her son Pedro, was deaf and became a nun, she wrote two works that place her among the first and most prestigious medieval women writers in the Spanish language. Plantilla:Secession == References ==

Selemoh ha-Leví, or Pablo de Santa María', initially Schlomo ben Jitzchaq ha-Levi (שלמה הלוי מבורגוס),[1] known as El Burgense (Burgos, around 1350-30 August 1435), was a poet, scholar and historian Spanish Spanish-Hebrew, Jew convert to Christianity, counselor of Enrique III, theological and biblical writer, bishop of Cartagena and commentator of Burgos. == Biography == He received a careful education in the Burgos Jewish school, from where he was a major rabbi, but, after the anti-Jewish revolt of 1391]] —known with the Central European term of [pogrom]]' or 'forced conversions of 5151' (corresponding year in the Hebrew calendar)—, started on June 6 of that year in Seville,[2] was converted by the preacher (saint)|Vicente Ferrer]] and, abandoning the Judaism, was baptized in the Catholic faith with the name of Pablo García de Santa María[3] in July 1390, shortly before the most terrible assaults on the Jewish wards of the entire Middle Ages in the year 1391. Having not wanted to become his wife, he separated judicially from her and educated his children, including the future humanist and bishop of Burgos Alfonso de Cartagena, in the Christian religion. His brother, Álvar García de Santa María, also converted. The ancient rabbi oriented himself towards Christian ecclesiastical life, studying theology in Paris and in Aviñón, city where the pontiff resided, who promoted him in 1395 to the dignity of archedian of Treviño (whose exercise had its headquarters in the Cathedral of Burgos, not in the County of Treviño). Enrique III proposed him for the bishopric of Cartagena (1401) and appointed him royal councilor and ayo of Prince Don Juan, future Juan II of Castile. In 1407, after the death of Pero López de Ayala, he was appointed chancellor mayor of Castile. He was also an advisor to Fernando de Antequera, king of Aragon. In 1415 he was elected bishop of Burgos. Two of his sons followed the ecclesiastical-political career, reaching various episcopal seats and responsibilities in Castilian politics: Alfonso de Cartagena and Gonzalo de Santa María. Months before his death he was appointed by Eugenius IV patriarch of Aquilea, being sueded in the Burgos headquarters by his son Alfonso, then royal ambassador at the Council of Basel. He moved away from courtly life and in his will left all his assets to the poor. He died on August 30, 1435 in the city of Burgos. His body was buried in the main chapel of the now disappeared convent of San Pablo de Burgos, of the Order of the Dominics. == Works == The seven ages of the world or Troubaded Ages is a poem in 339 coplas de arte major and verses dodecasílabos, in which the complete history of the world is made from the creation to the enthronization of the king Henri IV of Castile. It is dedicated to the mother of Juan II de Castilla Catalina de Lancáster in 1430, and although it was already composed according to its publisher Juan Carlos Conde between 1416 and 1418,[4] combining a story of universal history according to the topical seven ages of the world with a story of Castilian national history, he mentions the pope Calixtus III, who was only between 1455 and 1458, so what has come to us is a version of 1460 retouched, corrected and expanded after that date by an anonymous author, who also added comments and glosses in prose to other comments and glosses he already had. As for its formal aspects, it contains hardly any rhetorical ornaments: it looks like a versified and arid chronicle in a plain style. The work begins with a long exposition of Jewish history according to the Old Testament, then alternates the history of the Jews with a brief history of Greece, Rome and the Church, with the most important popes, and concludes with the history of the Visigothic kings and Castile by their monarchs, including his former pupil John II, whom he advises in terms of difficult interpretation and incites to conquer the kingdom of Granada. He does not mention the private don Álvaro de Luna. The poem was poorly attributed to Íñigo López de Mendoza, marqués de Santillana, when Eugenio de Ochoa printed it among the unpublished Rhymes of Don Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marqués de Santillana, of Fernán Pérez de Guzmán, Señor de Batres, and other poets of the 15th century (Paris: ed. of the author, impr. Fain and Thunot, 1844). Then it was edited by the Hispanic Raymond Foulché-Delbosc in the NBAE', XXII (1915) and the American Hispanicist M. Jean Sconza (Madison: HSMS, 1991), improving previous editions. Pablo de Santa María also wrote the Sum of Chronicles of Spain, the Generation of Jesus Christ and the Supper of the Lord. === Scrutinium Scripturarum === The 'Scrutinium Scripturarum contra perfidia iudaeorum' was composed in Latin at the end of his life, it is one for which it enjoys international fame, under the nickname of the "Burgense". He exposes in a dialogued way, first, the mistakes of the Jews, which he then refutes, and then explains the mysteries of the Christian faith. He reached several editions; the best known dates from 1591 and carries as a preamble his biography composed by Cristóbal de Santotis. From the same time are the aforementioned Additions ad postillam magistri Nicoali de Lyra super Bibliam (Additions to the Apostilles of the master Nicolas of Lira on the Bible) (1270-1340). == Pastoral work == He convened two synods. The one of 1418 reveals his interest in the correct formulation of the articles of the faith, revising the text of his predecessor Juan Cabeza de Vaca. The one of 1427 is of a pastoral and liturgical nature and had the participation of St. Bernardino of Siena. He financed part of the construction of the disappeared convent of San Pablo de Burgos, of the Order of the dominicos, strengthened the monastery of San Juan de Ortega carrying monks of Fresdelval, as well as San Miguel del Monte, next to Miranda de Ebro. In 1432 the monastery of claries of Nofuentes, dedicated to Our Lady of Rivas, received pontifical approval. == Relationship with Judaism == Pablo, who even after being baptized, continued to debate with several Jews, including Joseph Orabuena, chief rabbi of Navarra, and Joshua ibn Vives, became a bitter enemy of Judaism.[5] He did everything possible, frequently successfully, to convert their former co-religionists. With that same spirit and main purpose, as chancellor of the kingdom, he drafted an edict that was promulgated on behalf of one of the two regents: the widowed queen mother, Catalina de Lancaster, in Valladolid on January 2 (no. 12), to incite the conversion of the Jews of Castile. This law consisted of twenty-four articles aimed at completely separating Jews from Christians, paralyzing their trade and business, humiliating them and exposing them to contempt, forcing them to live in the narrow barracks of their guet or accepting the baptism. Driven by his hatred of Talmudic Judaism, he composed in the year before his death the Dialogus Pauli et Sauli contra judæos, the Scrutinium Scripturarum (Mantua, 1475, Mainz, 1478, Paris, 1507, 1535, Burgos, 1591), which served as a source to enfant the anti-Semitism of Alfonso de Spina, Gerónimo de Santa Fé and other Spanish writers hostile to the Jews, as well as that of Martin Luther in Germany, who composed under his inspiration the treatise 'On the Jews and their lies'. A few years after his baptism he wrote Additiones (which consist of additions to the postillas of Nicolás de Lira to the Bible, printed relatively frequently) and, already in his old age, a Universal History in Spanish verse, The Seven Ages of the World' or Troubad Ages. == Descendants == Along with him, his children and his mother were baptized. His firstborn, Gonzalo, was bishop of Astorga, of Plasencia and Sigüenza; while the third, Alonso, succeeded him in the headquarters of Burgos, an unusual fact, although not unique (see Spanish Clergy in the Old Regime). His wife would be baptized years later than him; and his father would never do it. Her granddaughter Teresa de Cartagena, daughter of her son Pedro, was deaf and became a nun, she wrote two works that place her among the first and most prestigious medieval women writers in the Spanish language. Plantilla:Secession == References ==

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library aus Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group

- ↑ Poliakov, Leon'The History of Anti-Semitism', Volume 2, pages 160-1 University of Pennsylvania Press: 2003

- ↑ {Netanyahu, B. [https:// House The origins of the Inquisition in the Spain] (1. edición). New York. pp. 171. ISBN 0-679-41065-1.

- ↑ «Introducción a Las Siete edades del mundo, by Pablo de Santa María. Recast of 1460». The Seven Ages of the World of Pablo de Santa María. Recasting of 1460. Lemir. January 30, 1997. Parámetro desconocido

|access date=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|apelidos1=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ de Madariaga, Salvador (1952). The life of the very magnificent Don Cristóbal Colón (en spanish) (5th edición). Mexico: Editorial Hermes. p. 178. «Don Pablo de Santa María was the head of the Spanish anti-Semitism in the fifteenth century.»

== Bibliography == * Serrano y Pineda, Luciano (1941) D. Pablo de Santamaría. Grand Rabbi and Bishop of Burgos. Speech read before the Royal Academy of History when entering it. by the Hon. and Revmo. ____, Abbot of Silos. Response to it from His Excellency Mr. D. Elías Tormo y Monzó, Academician of History. November 3, 1940, Burgos: Monte Carmelo Prints. * Cantera Burgos, Francisco (1952) Alvar García de Santa María and his family of converts. History of the Jewish quarter of Burgos and its most egregious converts. Madrid: Montano Institute. * id=ZDfs58BV-oUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=san+pablo+burgos&hl=es&ei=2jfES5ONEonr-QbN8rX7Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false El Convento de San Pablo de Burgos: Historia y Arte (1ª edición). Salamanca: Editorial San Esteban. 2003. ISBN 84-8260-118-0. Parámetro desconocido |apelidos= ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido |name= ignorado (ayuda) * Plantilla:Citation publication * Conde, Juan Carlos, The creation of a historiographical discourse in the Four hundred Castilian: the 'Seven Ages of the World' by Pablo de Santa María, Salamanca: University of Salamanca, 1999. * José del Collado, ed. (1824). id=vaYYsewsoQIC&pg=PA255&dq=monastery+trinidad+burgs+demolished&hl=es&ei=eX28S-eQLM-QsAal3-GuCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDYQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q&f=false España sagrada (2ª edición). Madrid. Parámetro desconocido |apelidos= ignorado (ayuda) * More bibliographic references in this note == See also == * Monastery of San Juan de Ortega. In 1431, Bishop Pablo de Santamaría regularized his situation. == External links == *

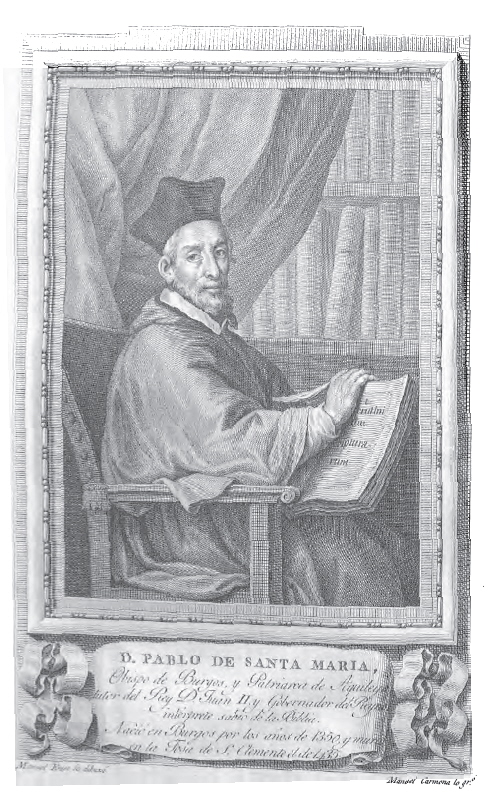

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Pablo de Santa María. * Online edition of The Seven Ages of the World * Portrait of Pablo de Santa María with an epitome about his life included in the book Portraits of illustrious Spaniards, published in the year 1791.

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Pablo de Santa María. * Online edition of The Seven Ages of the World * Portrait of Pablo de Santa María with an epitome about his life included in the book Portraits of illustrious Spaniards, published in the year 1791.