Jump Jim Crow

Jump Jim Crow es el nombre de un acto de vodevil blackface con música y baile realizado en 1828 por Thomas Dartmouth Rice alias "Daddy Rice", un actor estadounidense. El acto fue supuestamente inspirado por la canción y el baile de un esclavo negro con discapacidad física llamado Jim Cuff o Jim Crow, que diversas fuentes afirman que vivió en Saint Louis, Cincinnati o Pittsburgh.[1][2] La canción fue todo un éxito del siglo XIX y Rice interpretó su acto a lo largo del país, siendo conocido como Daddy Jim Crow.

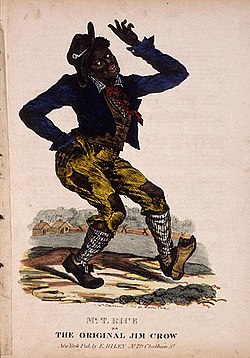

Portada de "Jump Jim Crow". | ||

| Autor | "Daddy Rice" | |

|---|---|---|

| Año | 1828 | |

| Género | Vodevil | |

| Publicación | ||

| Año de publicación | 1832 | |

| Idioma | inglés | |

| Música | ||

| Compositor | Thomas Dartmouth Rice | |

"Jump Jim Crow" fue el primer paso clave en una tradición de la música popular estadounidense que se basaba en la "imitación" de los negros. La letra de la canción fue publicada por primera vez a inicios de la década de 1830 por E. Riley. En un par de décadas este género alcanzaría una gran popularidad con el auge del minstrel.

Debido a la fama de Rice, para 1838 el término "Jim Crow" se convirtió en una forma peyorativa de nombrar a los afroamericanos[3] y dio su nombre a las leyes de Jim Crow, que fueron la base de la segregación racial en el sur de los Estados Unidos desde 1876 hasta 1965.

Letra de la canción

editarLa canción original impresa empleaba "estrofas flotantes", que aparecen de manera alterada en otras canciones populares. El coro de la canción está muy relacionado con las tradicionales Uncle Joe / Hop High Ladies; algunos folcloristas consideran que Jump Jim Crow y Uncle Joe son parte de una familia de canciones.[4]

La letra citada con más frecuencia es la siguiente:

- Come, listen all you gals and boys, Ise just from Tuckyhoe;

- I'm goin, to sing a little song, My name's Jim Crow.

- CORO [después de cada estrofa]

- Weel about and turn about and do jis so,

- Eb'ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.

- I went down to the river, I didn't mean to stay;

- But dere I see so many gals, I couldn't get away.

- And arter I been dere awhile, I tought I push my boat;

- But I tumbled in de river, and I find myself afloat.

- I git upon a flat boat, I cotch de Uncle Sam;

- Den I went to see de place where dey kill'd de Pakenham.

- And den I go to Orleans, an, feel so full of flight;

- Dey put me in de calaboose, an, keep me dere all night.

- When I got out I hit a man, his name I now forgot;

- But dere was noting left of him 'cept a little grease spot.

- And oder day I hit a man, de man was mighty fat

- I hit so hard I nockt him in to an old cockt hat.

- I whipt my weight in wildcats, I eat an alligator;

- I drunk de Mississippy up! O! I'm de very creature.

- I sit upon a hornet's nest, I dance upon my bead;

- I tie a wiper round my neck an, den I go to bed.

- I kneel to de buzzard, an, I bow to the crow;

- An eb'ry time I weel about I jump jis so.

Otras estrofas, citadas en inglés estándar no dialectal:

- Come, listen, all you girls and boys, I'm just from Tuckahoe;

- I'm going to sing a little song, My name's Jim Crow.

- Coro: Wheel about, and turn about, and do just so;

- Every time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.

- I went down to the river, I didn't mean to stay,

- But there I saw so many girls, I couldn't get away.

- I'm roaring on the fiddle, and down in old Virginia,

- They say I play the scientific, like master Paganini,

- I cut so many monkey shines, I dance the galoppade;

- And when I'm done, I rest my head, on shovel, hoe or spade.

- I met Miss Dina Scrub one day, I give her such a buss [kiss];

- And then she turn and slap my face, and make a mighty fuss.

- The other girls they begin to fight, I told them wait a bit;

- I'd have them all, just one by one, as I thought fit.

- I whip the lion of the west, I eat the alligator;

- I put more water in my mouth, then boil ten loads of potatoes.

- The way they bake the hoe cake, Virginia never tire;

- They put the dough upon the foot, and stick them in the fire.

Variantes

editarMientras era expandida desde una sola canción hasta un espectáculo minstrel completo, Rice habitualmente escribía estrofas adicionales para "Jump Jim Crow". Las versiones publicadas en aquel entonces tenían una extensión de hasta 66 estrofas; una versión de la canción archivada por American Memory tiene 150 estrofas.[5] Las estrofas iban desde las libres de la versión original hasta apoyar al Presidente Andrew Jackson (conocido como "Old Hickory"); su oponente Whig en las elecciones de 1832 fue Henry Clay:[6]

- Old hick'ry never mind de boys

- But hold up your head;

- For people never turn to clay

- 'Till arter dey be dead.[7]

Otras estrofas, también de 1832, expresaban sentimientos antiesclavistas y de solidaridad interracial que escasamente aparecían en el minstrel blackface posterior:[7]

- Should dey get to fighting,

- Perhaps de blacks will rise,

- For deir wish for freedon,

- Is shining in deir eyes.

- And if de blacks should get free,

- I guess dey'll see some bigger,

- An I shall consider it,

- A bold stroke for de nigger.

- I'm for freedom,

- An for Union altogether,

- Although I'm a black man,

- De white is call'd my broder.[7]

Origen del nombre

editarEl origen del nombre "Jim Crow" es incierto, pero pudo haber evolucionado a partir del uso del peyorativo crow para referirse a los negros en la década de 1730.[8] Jim puede haberse derivado a partir de "jimmy", un viejo término del argot para la pata de cabra, basado en un juego de palabras con el nombre de la herramienta en inglés (crowbar). Antes de 1900, las patas de cabra eran llamadas "crow", mientras que una pata de cabra corta aún es llamada "jimmy", una típica herramienta de ladrones.[9][10][11] El concepto popular de un cuervo bailando es anterior al acto de Jump Jim Crow y tiene sus orígenes en la práctica de los antiguos granjeros de empapar maíz con whisky y dárselo a los cuervos. Los cuervos comían el maíz y se emborrachaban a tal punto que no podían volar, pero giraban y saltaban indefensos cerca del suelo, donde el granjero podía matarlos con una porra.[12][13][14]

Véase también

editarReferencias

editar- ↑ «An Old Actor's Memories; What Mt. Edmon S. Conner Recalls About His Career.» (PDF). The New York Times: 10. 5 de junio de 1881. Consultado el 10 de marzo de 2010.

- ↑ Hutton, Michael (junio–diciembre de 1889). «The Negro on the Stage». Harpers Magazine (Harper's Magazine Co.) 79: 131–145. Consultado el 10 de marzo de 2010., see pages 137-138

- ↑ Woodward, C. Vann and McFeely, William S. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. 2001, page 7

- ↑ «Alternative lyrics at Blugrassmessenger.com». Archivado desde el original el 15 de agosto de 2023. Consultado el 8 de diciembre de 2016.

- ↑ «Alternative lyrics at Blugrassmessengers.com». Archivado desde el original el 15 de agosto de 2023. Consultado el 8 de diciembre de 2016.

- ↑ Strausbaugh, 2006, pp. 92–93

- ↑ a b c Strausbaugh, 2006, p. 93

- ↑ I Hear America Talking by Stuart Berg Flexner, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1976, page 39; possibly also Robert Hendrickson, The Dictionary of Eponyms: Names That Became Words (New York: Stein and Day, 1985), ISBN 0-8128-6238-4, possibly page 162 (see edit summary for explanation).

- ↑ Lockwood's dictionary of terms used in the practice of mechanical engineering by Joseph Gregory Horner (1892).

- ↑ For example, in the New York statutes on burglary it reads: "...having in his possession any pick-lock, key, crow, jack, bit, jimmy, nippers, pick, betty or other implement of burglary..."

- ↑ John Ruskin in Flors Clavigera writes: "...this poor thief, with his crow-bar and jimmy" (1871).

- ↑ "Sometimes he made the crows drunk on corn soaked in whiskey, and as they reeled among the hillocks, knocked them on the head", "A Legend of Crow Hill". The World at Home: A Miscellany of Entertaining Reading. Groombridge & Sons, London (1858), page 68.

- ↑ "Somebody baited a field-fall of crows, once, with beans soaked in brandy; whereby they got drunk.", "Talking of Birds". The Columbian Magazine, July 1844, p. 7 (p. 350 of PDF document).

- ↑ “Soak a few quarts of dried corn in whiskey, and scatter it over the fields for the crows. After partaking one such meal and getting pretty thoroughly corned, they will never return to it again.” The Old Farmers Almanac, 1864.

Bibliografía

editar- Scandalise My Name: Black Imagery in American Popular Music, by Sam Dennison (1982, New York)

- Strausbaugh, John (2006). Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture. Jeremy P. Tarcher / Penguin. ISBN 1-58542-498-6.

Enlaces externos

editar- Letras y trasfondo en Bluegrass Messengers (en inglés)